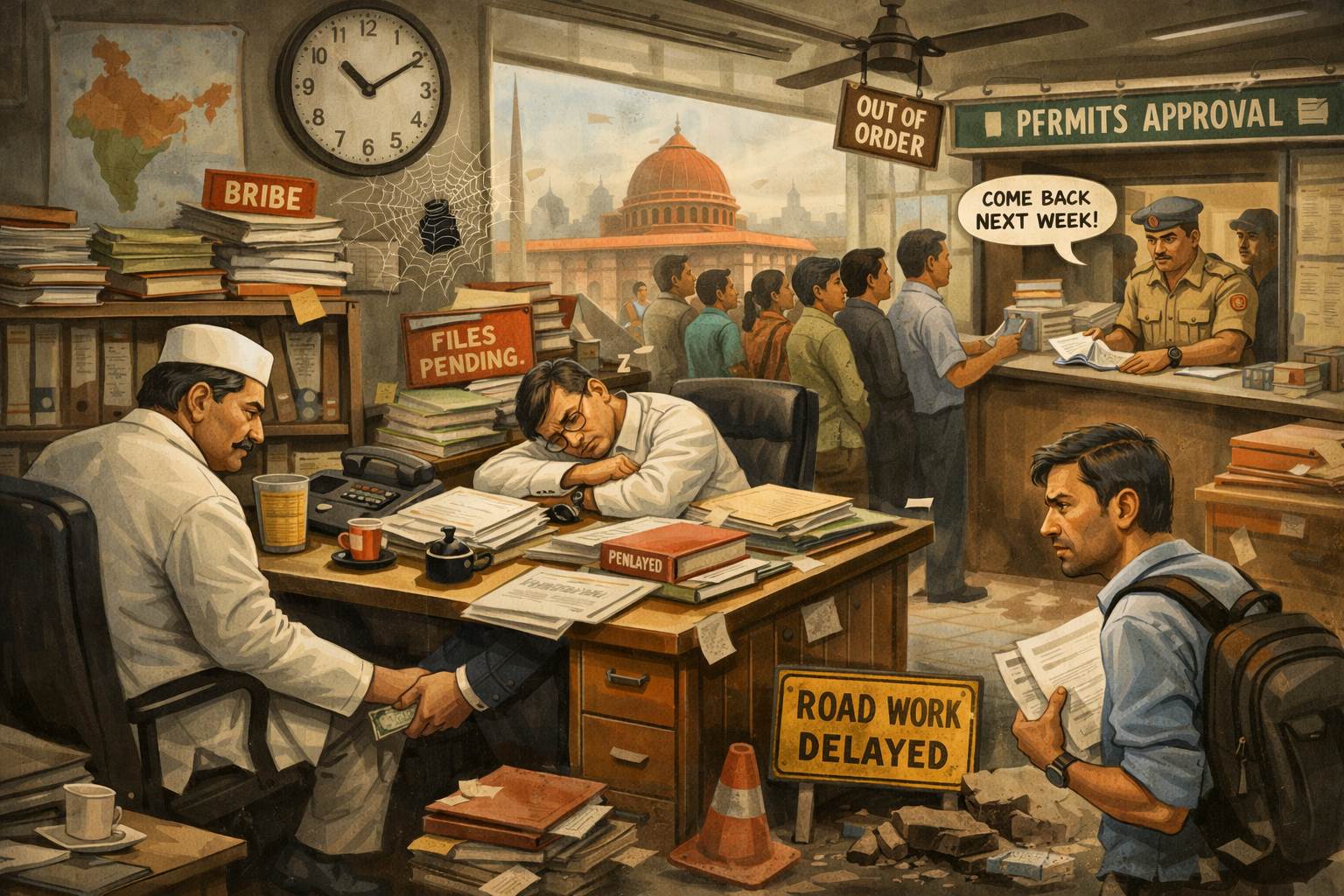

I’ve often wondered how we, as the world’s fastest-growing major economy, the largest democracy, and with tens of millions of educated, capable people, can be so hopelessly inefficient at governance. I know, the easy answer is that we have bad and corrupt politicians, who are, in turn, supported by thousands of government servants practising bribe-taking as a lucrative side hustle. But how did it really come to this?

Greed is a basic human psychology, and it’s not restricted to us Indians. So is the tendency to cut corners and find the easy way out, or to prioritise self-interest above everything else. Anything rooted purely in human behaviour can’t be the driving factor. There must be something wrong with our design.

And there indeed is, in several ways. Let’s go back in time a bit to understand this.

~

In 1947, India didn’t inherit a well-oiled nation from the British. What we got instead was an extraordinarily fragmented geography: people practising multiple religions, speaking dozens of languages, following hundreds of customs and cultures, and organised around complex social hierarchies. Very little bound these people together, except perhaps the idea that they were all going to be part of a country called India (or Bharat or Hindustan). Even that wasn’t certain.

Wherever there’s heterogeneity, the level of trust naturally drops. Unfamiliarity breeds suspicion. It’s like different tribes coming together. Each stays on guard, wary of letting it down until safety feels assured. India has always been such a place. But back then, without the information and exposure people have today, you can imagine the subconscious mistrust this must have bred.

What made this significantly worse, and much harder to overcome, was that we were illiterate and extremely poor. Over two centuries, the British had stripped India of everything that attracted them here in the first place.

When independent India’s founders took charge, they weren’t governing from a position of confidence. There was real fear that the country might not hold together. Political unity was far from guaranteed.

To give her the best chance of success, everything needed to be controlled from the Centre. Centralised economic planning was necessary for a poor country that needed scale, coordination, and rapid development. Socially, it was crucial not to let local elites wreak havoc with regressive practices. Discrimination based on caste and gender is prominent even today, but back then it was simply a way of life. Perhaps that’s why Dr Ambedkar remarked, “What is the village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and communalism?”

Everything important for the progress of the nation needed to remain under central control, where a few wise people could steer this mammoth ship in the right direction.

The choices made then were right for that time.

The problem is, the world moved on, India moved on, but the choices stayed. What brought stability almost eight decades ago causes frustration today.

~

In most large countries, local governments do the bulk of the work. They run schools, manage roads, maintain sanitation, issue permits, regulate local commerce, and deliver public services. Naturally, they also control a significant share of public money and employ most government workers.

India is a stark exception.

Local governments in India account for only about 3 percent of total public expenditure. In China, local governments spend over 50 percent. In the United States and Brazil, the figure is closer to 25–30 percent. Even countries far smaller and less complex than India devolve far more financial authority to the level closest to citizens.

The same pattern appears in public employment. In the US and China, over 60 percent of government employees work at the local level. In India, that number is closer to 10 percent. The people responsible for fixing roads, managing cities, enforcing rules, and improving ease of living simply do not have the staff, the money, or the authority to do their jobs well.

This is the root of the dysfunction people experience daily. Local officials are expected to execute but have zero stake in outcomes. There is absolutely no incentive to improve them. Whether a city functions smoothly or descends into chaos has little bearing on careers, compensation, or advancement. The system is designed for complacency.

When effort and outcomes are disconnected, we end up relying purely on the personal righteousness of individuals to do their jobs well. That is not a great strategy, especially when existing precedents have already set a low bar. Bribes, in this context, are not just a moral failure. They are a response to a system that offers no legitimate upside for doing better.

Our contrast with China is especially instructive. At the heart of its system is a formal cadre evaluation mechanism, where local officials are assessed on clear, measurable outcomes. Metrics such as GDP growth, investment attracted, industrial output, employment creation, and fiscal revenue form a significant part of an official’s performance score. Officials who deliver results move to larger cities or provinces. Those who don’t see their careers stall. Mayors and party secretaries are treated like CEOs of territories, with growth as their key performance indicator.

This has created healthy competition between cities and regions. In the early 2000s, cities like Suzhou, Wuxi, and Hangzhou, all relatively similar at the time, actively competed to attract manufacturing, foreign investment, and talent. Each experimented with industrial parks, tax incentives, land policies, and faster approvals. When Suzhou’s industrial park model succeeded, it wasn’t just rewarded locally; its template was replicated across the country. This is just one of many successful examples.

Importantly, in China, growth has an owner. If a city performs well, its leadership gains both resources and career progression. It doesn’t mean that corruption has disappeared, but incompetence has certainly become costlier.

India inverted this model. We centralised authority but decentralised responsibility. The Centre announces grand visions, while execution is left to underpowered local bodies that lack both incentives and accountability. Control flows downward, but responsibility never quite settles anywhere. China’s example shows what’s possible with the right structure.

Incentives predict behaviour far better than vision or intention ever can. We cannot change human nature, but we can design systems that bring out the best in people. Unfortunately, what once helped India stay together now prevents it from working better. The question is, is anyone even thinking about this?

What do you think?

It’s a hypothetical question, but in your view,

Will rethinking the incentive structure bring about a significant change in how the country is run?

Write to us at plainsight@wyzr.in.

What we’re reading

Accelerating India’s Development by Karthik Muralidharan. I can’t think of any book that explains the problems with India’s governance with such depth and clarity. One of those books that single-handedly make you smarter.

Until next time.

Best,